- Home

- Rachel Hawkins

Journey's End Page 2

Journey's End Read online

Page 2

CHAPTER 2

“SO YOU’RE SURE PEOPLE LIVE HERE?” NOLEN STANHOPE asked her father as they drove down the bumpy road leading to Journey’s End. A few houses dotted the landscape, but they were hardly more than blurry shapes in the fog, and Nolie leaned closer to the window, her breath making its own fog. “On purpose?”

The car hit another pothole, and Nolie jounced in her seat, running her finger through the little cloud she’d made on the glass.

“Yup,” her father told her, pushing his glasses up his nose with one finger. “Few hundred of ’em.”

Nolie knew that, of course. When she’d heard she’d be spending the summer with her dad, out here literally at the end of the world, she’d done her reading. What she’d learned had made her a little less excited for this trip: there were 453 people currently living in the village of Journey’s End, it rained roughly 300 days of the year, and even in the height of summer, temperatures rarely rose above sixty degrees Fahrenheit.

At home in Georgia, the summers were hot and sweaty and smelled like chlorine and freshly cut grass.

In Scotland, the salty scent of the sea snuck in despite the rolled-up windows, and underneath that, another, bitter smell. Almost like smoke.

Nolie liked it.

And she liked the idea of being here in Scotland for the summer. Back home, she’d be spending June through August trying not to die of heatstroke and talking her mom out of sending her back to those weird little day camps at the community center. Learning how to make decoupage boxes had been fun when she was ten or eleven, but now that she was twelve? International travel seemed like a much better way to spend the summer.

Tearing off the sticker that announced she was an Unaccompanied Minor, she turned back to the book in her lap, a collection of ghost stories her dad had brought her when she’d met him at the airport in Inverness. “I remembered you liked spooky things,” he’d told her, and she’d grinned. Nolie didn’t just like spooky things; she loved them. Her favorite TV shows all involved people with night-vision cameras and EVP recorders in scary old houses, and she’d actually loaded five episodes of Chasing Spirits on her phone before leaving for Scotland.

Her dad, being a scientist, had never been all that crazy about ghosts or monsters, so she thought the book might be a kind of peace offering, a “hey, sorry I haven’t seen you in six months because I was in Scotland studying fog” present.

He’d also brought her a stuffed animal, a sheep wearing a little blue T-shirt that read Stand baaaaack!

Apparently that was supposed to be some sort of joke about “the Boundary,” the big fog bank off the coast that her dad had come here to study. She’d read a lot about that, too, wanting to know just what it was about this place her dad found so fascinating. She’d only had to look at a couple of websites before she totally got it. The Boundary was like the Bermuda Triangle, a place where people went missing with no real explanation. And it had just showed up a few hundred years ago, out of nowhere, upping the whole Super Creepy and Mysterious thing a lot.

Still, selling sheep with T-shirts joking about it seemed a little weird. Maybe that was what people thought was funny out here in . . . could you even call a place like this “the boonies”? She would have said that at home, but it usually referred to a place in the country where everyone lived in trailers and had cows. This place seemed even farther away than that, and Nolie wasn’t sure there was a word for what Journey’s End was.

Nolie turned to her dad. “Mom said the house is on the beach?” She’d been looking forward to that. The water would be too cold for swimming, but she could still wrap up in a sweatshirt and watch the ocean.

Her dad nodded. “It is, yeah. But the fog is so thick that you wouldn’t even know the Caillte Sea was there if you couldn’t hear it.”

Nolie had known the name of the sea from the books she’d read, but she’d been pronouncing it “KALE-teh.” In her dad’s mouth, the word came out more like “Kyle-che,” and Nolie sighed. She hadn’t realized coming here would involve learning a whole new language, too.

“Caillte,” she repeated, trying to get it right, and her dad smiled, showing off his slightly crooked front teeth. Like Nolie, his eyes were blue and there was a smattering of freckles across his cheeks. Underneath his cap (this totally embarrassing plaid thing that made him look like an old-fashioned newspaper boy), his hair was a lighter shade of Nolie’s own bright red.

His eyebrows were red, too, and he waggled them over his glasses at Nolie now. “Good job, kiddo. We’ll have you talking like a local before you know it.”

Her dad turned left onto something he called the “high street,” but it was actually pretty low, the road curving down into a valley, and green hills rising up on both sides, cutting off Nolie’s view of the ocean.

As her dad stopped the car to let an older lady with bright yellow shopping bags cross the street, Nolie noticed a man standing on the sidewalk, his arms crossed over his chest as he looked at their car. Well, at her dad, really. The man’s face was red, a cap pulled low over his eyes, but Nolie didn’t miss the glare he was currently giving them.

And when she looked back out the windshield, the lady passing in front of them was scowling, too.

Nolie’s dad sighed.

“Just a heads-up, kiddo,” he said. “I’m not exactly the most popular guy in Journey’s End at the moment.” The car was lurching forward now that the way was clear.

“It’s not a big deal,” he went on to say, drumming his fingers on the steering wheel. “Just that things between the Institute and the town have always been a little tense, and lately, they’ve been really tense. We’ve been trying some new experiments, testing out new equipment, and no one in town is really a fan of that.”

“Why not?” Nolie asked.

Her dad shook his head. “Lots of reasons, I think. Main one being that if we actually figure out what’s causing the fog, it might make it seem a little less mysterious, and that could affect tourism. That’s how most of the people in town make their money, chartering boats out to see it, selling stuff like that.” He nodded at the book and the sheep in her lap. “So if you see me getting ugly looks, that’s all it is.”

“I figured it was about your hat,” Nolie joked, and her dad looked over at her, smiling.

“I’ll have you in one of these hats before the summer is out, just you wait,” he promised, and Nolie grinned back.

The car was moving uphill now, and once again, the Caillte Sea spread out below them, gray and rocky.

“What does it mean?” Nolie asked. “Caillte?” The car drove slowly past a lot of gray brick buildings with big front windows that all displayed a lot of plaid, and in one, some cheap plastic beach toys, too. Where was Ye Olde Walmart? Nolie wondered. Surely people in Journey’s End needed stuff.

“It means ‘lost,’” Dad replied, just as the car passed a place called Gifts from the End of the World. Judging from the display in the window, that was where Nolie’s stuffed sheep had come from, and she twisted in her seat, trying to get a better look into the shop. But then they were turning again, following a narrow road out of the main village and up toward the cliffs.

“That’s kind of creepy.” The car hit another pothole, and Nolie nearly bit her tongue. “The Lost Sea.” It made her shiver to say it, but in the good way. Definitely the kind of place where an episode of Chasing Spirits could happen. Did they sell night-vision cameras around here?

Nodding, her dad turned down another lane, this one covered in gravel that rattled underneath the tires. “The name is creepy, but fitting. Lots of people have gotten lost out there.”

Nolie thought about mentioning that people went missing in every ocean ever, but she was afraid that would sound mean, so she just made an agreeing noise and propped her heels on the edge of her seat.

They rattled and bumped down the lane, twisting and turning, until her dad pulled up in fron

t of a big white house with navy shutters and a wraparound front porch. It was narrow, but tall, and looked a lot older than the house Nolie shared with her mom back in Georgia.

Her dad must have read her thoughts, because as they got out of the car, he smiled and said, “Built in 1854. Which actually makes it one of the newer houses in Journey’s End.” He gestured farther down the cliff, and Nolie saw several other houses that looked almost identical to this one. “The Institute bought all of them when they set up the research center here. Uses them as homes for those of us who work out here full-time.” He pointed to another house, far enough away that it was only a white dot against the bright green of the hills. The house was situated on a little rise and closer to the cliffs than the others. “That’s it right there,” he told her. “The Institute.”

“It’s just another house,” Nolie said, and her dad gave an easy shrug.

“We’ve never been able to get a permit to build a new building, so we use what we can. It’s the second-biggest house in Journey’s End.”

Turning, Nolie pushed her hair back from where it was blowing in her face. “What’s the biggest one?”

Dad smiled and folded his arms on top of the car. “Old manor house on the outskirts of town. You’d like it.”

Nolie made a mental note to see it when she got a chance.

For now, she walked past the car and skirted the house altogether, walking around the side where she could get a view of the ocean and the massive, rolling fog bank a few miles out.

“That’s it, huh?”

At first glance, the Boundary just looked like fog. Lots of it, sure, blotting out the horizon, rising to the sky, stretching so far that Nolie couldn’t see past it on either side, but the longer she stared at it, the stranger it seemed. It was thicker than any fog she’d ever seen, and it seemed to roll and churn without actually moving forward.

Her dad clapped a hand on her shoulder, and Nolie leaned toward him a bit. It was nice, finally being with her dad after six months of not seeing him, and until this second, she hadn’t realized how much she’d missed him.

“That’s it,” he confirmed, and when she looked up at him, he was grinning dreamily out at the sea, like he was looking at a puppy or a pretty girl or anything but a giant cloud of fog that maybe ate people.

“It doesn’t look so scary,” Nolie lied.

Dad laughed. “It’s not supposed to be scary. Not anymore, at least. It’s fascinating and mysterious, but not scary.”

Nolie wasn’t sure how fascinating it was, but it was definitely mysterious. A giant ball of fog that had hovered there off the shore since who knew when, apparently. A big mass of cloud that, if you sailed into it, wouldn’t let you sail back out. There was even a no-fly zone established over it since a few planes had gone missing back in the seventies. But then, for the most part, no one ever had a reason to fly over this tiny spit of land. Not for the first time, Nolie wondered why this big wall of mist was so much more interesting to her dad than anything in Georgia.

More interesting than Nolie and her mom.

“I could take you over to the Institute later,” Dad offered. “Show you a little bit of what I do out here.”

Nolie had taken three separate flights just to get to Scotland, and then there’d been the three-hour drive to Journey’s End. She was tired and weirded out, and had a little bit of a day-after-Christmas feeling going on.

“I think I want to just hang out for now,” she said, shaking her head.

The frown that crossed her dad’s face was only there for a second, but Nolie saw it, and it made her feel guilty.

“Can I walk down to the beach?” she asked, hoping that might make him happy. That way, she could still be alone, but she wouldn’t be sulking in her room, or making him think she was disappointed. She’d be exploring.

Nolie could see her dad thinking about it, and she moved a little closer. “I promise not to get in the water.”

That made Dad smile a little. “Oh, I’m not worried about that. You dip one toe in, you’d run out screaming. It almost never goes above about fifteen degrees, even in the summer.”

“Fifteen?” Nolie asked, looking back out at the water, trying to imagine how it could be that cold in the summer.

“Oh, sorry,” her dad said, shaking his head. “Fifteen degrees Celsius. That’s about sixty degrees to you.” Nolie wrinkled her nose at that. Sixty degrees was better than fifteen, but still. What was the point of a beach if you couldn’t swim in the ocean? Mom always took her to Tybee Island in the summer, where the ocean felt like a bath, and the sun made freckles pop out on her shoulders and the bridge of her nose.

But after all those hours on planes, Nolie could use some quiet time to stretch her legs.

Even if it was on a frozen beach with man-eating fog.

But before Dad could give her a yes or no, the phone attached to his belt rang. He held up one finger, answering it while Nolie looked back at the sea.

She wondered just how many people had been lost. Her dad had said there was a memorial in town, and they kept records at the Institute. She definitely wanted to check that out.

A movement down on the shore caught her eye, and Nolie leaned a little closer. Looked like she wasn’t the only one who’d thought about taking a walk today. A boy was wandering along the water’s edge. It was foggy down there, but not too bad, and she could see his dark hair, make out the puzzled expression on his face when he glanced up toward the cliffs. He was dressed awfully well for beach strolling, in Nolie’s opinion, and she wondered if that was another thing she needed to learn about Journey’s End. Did everyone go to the beach in their Sunday best?

Turning back to her dad, Nolie decided she didn’t want to walk on the beach after all. But it apparently didn’t matter, since he was already moving back to the car, waving for her to follow him. “The Institute,” he said by way of explanation. “Need to get back for a little bit.”

“Why?”

Her dad wiggled the cell phone at her. “Not sure, really. Connection cut out before Burkhart could tell me what was going on. That’s the problem with Journey’s End; phones never work quite right. Same for TV and the internet.”

“Right,” Nolie said. “Mom mentioned that. She even bought me a stationery set so I could write letters.” Mom had actually promised to send a letter as soon as Nolie left, so she was hoping to get one soon. As nice as it was to be spending time with Dad again, she already missed her mom.

Dad raised his eyebrows. “That’ll be fun, then. Very oldschool. We do get fairly decent internet at the Institute, so if you wanna email your friends or . . . or Facebook or—”

“I’m twelve, Dad. Mom lets me stay at our house by myself all the time.”

But Dad just gave an easy shrug. “That’s your mom,” he said. “Go ahead and get in. We won’t stay too long.”

“I’m tired, Dad,” she argued. “And, I mean, no offense, but I don’t feel like hanging out in your office today.”

She expected a fight, but instead, Dad walked around and opened her car door—the wrong side; she wasn’t sure if she’d ever get used to that—and said, “Make you a deal: I’ll drop you in the city center. You can look around, and I won’t be gone long.”

Nolie thought about mentioning that she’d probably be safer in his house than wandering a strange village on her own, but looking around did sound better than going to work with her dad. She slid back into the car seat and closed her door, her book of ghost stories and stuffed sheep tumbling to the floorboard.

“I’ll bring you up to work tomorrow,” Dad offered, “after you’ve had a chance to get your feet back under you.”

As they drove down the hill, she turned to look over her shoulder. From this angle, she couldn’t see the water, and she thought again of that boy on the beach. She could have sworn he’d been wearing suspenders. Was that a Scotti

sh thing?

The water out of sight, the only thing Nolie could see now was the fog—the Boundary—up beyond the green hill.

CHAPTER 3

BEL KNEW IT WAS WEIRD TO HAVE A FAVORITE DEAD person, but since she spent every afternoon looking at pictures of dead people, it was bound to happen.

She moved her dust cloth over the boy’s photograph, making sure the glass was extra shiny. The little plaque under his frame declared that his name was Albert MacLeish, but Bel knew everyone had called him Al. He’d died in 1918, and there was no one from his family left in Journey’s End, but Bel had spent most of her life looking at his face on the back wall of her parents’ souvenir shop, so she felt pretty confident that he was an Al. There was something about his eyes and the way he was smiling without seeming to smile that struck Bel as . . . Al-ish.

“There you go, Al,” she said out loud, giving his frame one more polish. “Spic-and-span.”

Moving on to the next photograph, Bel sighed. If Al was her favorite dead person, Edna Herbert, 1860–1918, was her least. She didn’t like the old woman’s scowl or how tight her bun was.

So Edna didn’t get much of a shine, but Davey McKissick (1898–1918) did, especially since he had been Bel’s great-grandfather’s uncle. Bel was also careful to give Al’s brother, Edward (1900–1918), some extra attention. All in all, there were six photo portraits at the back of the shop, reminders of an awful year when the Boundary had been more troublesome than ever before. Of course, a lot more than six people had died in the choppy waters of the Caillte Sea over the years, but these were the people the village still remembered, and Bel liked that when her grandad opened this shop, he’d decided to make a wee memorial for them.

Of course, it was a bit tacky that the memorial was the back wall of Gifts from the End of the World, and those somber faces were crammed in with shelves of snow globes and stuffed sheep wearing T-shirts, but no one had ever suggested moving the pictures elsewhere.

Bel’s mum said it was because the village wanted all those tourists to remember that this was a dangerous place. A sad place, sometimes. But when Bel watched people’s eyes skate over the wall of photos as they dug through a display of silly socks, she wasn’t sure the memorial was serving its purpose.

Rebel Belle

Rebel Belle Royals

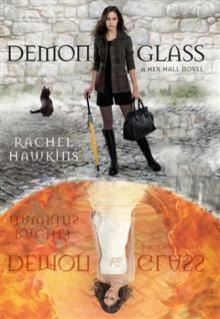

Royals Demonglass

Demonglass Hex Hall

Hex Hall Spell Bound

Spell Bound Her Royal Highness

Her Royal Highness The Wife Upstairs

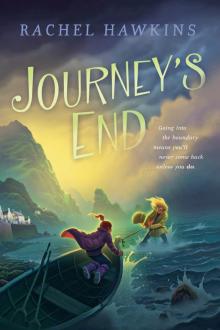

The Wife Upstairs Journey's End

Journey's End School Spirits

School Spirits Miss Mayhem

Miss Mayhem Lady Renegades

Lady Renegades Hex Hall Book One

Hex Hall Book One Demonglass hh-2

Demonglass hh-2